Dreaming of Heathcliff's dogs chasing Michael Gove

In the week that the (unelected) Prime Minister of the UK intends to trigger Article 50 that begins the country’s negotiations to separate from the European Union, I’m going to type whatever comes out in a stream of consciousness. My past few blogs have been about writing, Emily Brontë and Wuthering Heights in particular. I wonder whether Heathcliff looking through the windows of Thrushcross Grange and despising the spoilt lives of privilege is a common experience. Is that why 52% (of the voters who bothered to vote) voted to Brexit? Would Heathcliff have voted to leave the European Union? (In truth, I don’t think he would have voted; he might have set his dogs on Michael Gove…. Or set fire to the polling booth….)Do we want a return to the feudal system?

In the past it was easier to understand Britain’s/England’s/the UK’s social system:

- Before the Norman Conquest in 1066 there were serfs (slaves), cottars (cottagers), ceorls (freemen), thanes (landowners), earls and other nobles, royalty and the king

- In medieval times the feudal system dominated: serfs now had villeins below and peasants above; freemen came after yeomen came after servants; then came knights and vassals before the nobles and the king

- Both pre-1066 and post-1066 there was a parallel hierarchy in the Church too with the Monks after the Priests after the Dean after the Prior after the Abbot and then the ArchDeacon, Archbishop, Bishop, Cardinal and Pope (and then Henry VIII complicated everything by divorcing and beheading his spouses and inventing the Church of England)

Knowing your place

The four seismic shifts since Medieval Times that have affected the UK’s class system are the Industrial Revolution, World War One, World War Two and Globalisation. Before the Industrial Revolution it was easy to know your place: your goods and lands were your own as long as you gave up a portion to the level above you (a portion either in cash, goods or a willingness to supply male bodies to fight in wars.) Apart from in times of famine – or catastrophic upheavals like the Black Death – people lived lives “sufficient unto themselves.” The sons of blacksmiths generally became blacksmiths; the youngest sons of nobles generally went into the church; the lives of non-religious women generally focused on giving birth. Occupation, social status and political influence were the anchors of society. You only broke the mould if someone on a higher plane of the structure conferred some favour upon you in terms of land or status. Do Brexiters want to return to this period of our history?The Age of Reason

The Industrial Revolution brought wealth to unexpected people in unexpected ways. Suddenly ordinary people could make swift profits through inventions and hard word. Mass migration of people to factories in cities disrupted the equilibrium in the towns and villages. Ideas from the French and American revolutions trickled through the brains of thinkers and agitators and God was on trial for His/Her/Its very existence as the Church began to lose its influence over society. The Age of “Reason” or “Enlightenment” had arrived. The old ways were being disrupted. But the peasants/working class were still labouring in filthy conditions, underpaid, underfed, uncared for in terms of health, safety and welfare and likely to die from dysentery or diphtheria or cholera. Do Brexiters want to return to this period of our history?The Années Folles

The Middle Classes (old cottagers and freemen) began to find political voices and by the time of the First World War the demand for women’s equality was a clarion call. There was no turning back and universal suffrage and meritocracy meant it was possible to use the capitalist system in most of the world (or, clandestinely, a corrupted version of the communist system in the USSR; or, strangely, a smoke and mirrors version of communism in China) to beat the system and rise to the top from wherever you started. You just needed to know how to play the system. So – just after the First World War – that seemed like a good time to be alive – the Jazz Age, the Roaring Twenties, the French called it the Crazy Years (Années Folles).I could understand if Brexiters wanted to return to this period of our history (as long as what came next could be avoided.)Ralph wept for the end of innocence, the darkness of man’s heart

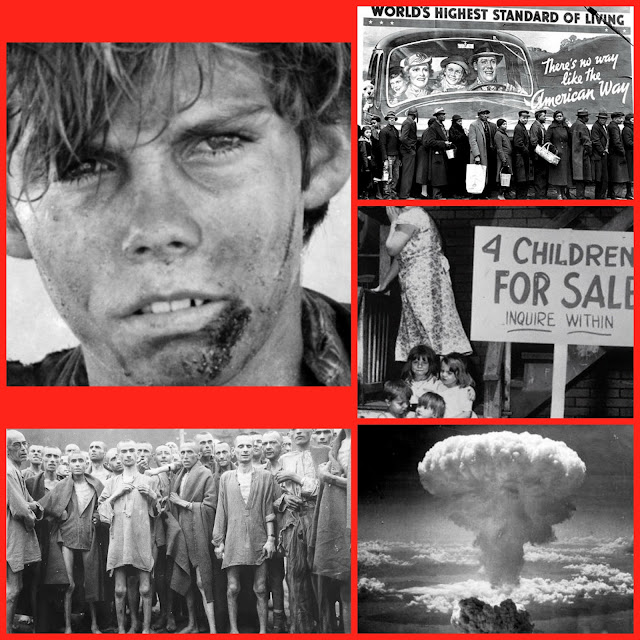

The 1930s, tragically, brought the financial crash (sound familiar?) that led to The Great Depression that led to the rise of Fascism that led to The Second World War, the holocaust and the atomic bomb. The peace at the end of World War One had clearly been an attempt to impose outdated terms on political systems in countries whose societies were going through convulsions. The Roaring Twenties may have been the period, after all, of the greatest ostrich-head-in-the-sand national-delusion. And after World War Two all the certainties about “isms” became uncertainties and the world had faced, as Ralph weeps at the end of Golding’s 1954 Lord of the Flies:the end of innocence, the darkness of man’s heartSurely Brexiters don’t want to return to the 1950s, or do they?

|

| James Aubrey as Ralph in Peter Brook's 1963 film of Lord of the Flies with images of the end of innocence, the darkness of man's heart |

Taking back control or business as usual….?

Much good followed the Second World War – attempts to build global organisations to end poverty and improve health on an international scale. There was an upsurge in cultural sharing and tourism that improved understanding between nations. Great strides were made in treating all citizens equally with reforming legislation about gender, race, disability, sexuality, age and religion. It once again seemed possible that, with the age of the internet, we might all be able to work more efficiently for fewer hours and enjoy more leisure time. If everyone worked fewer hours more people could be employed. As computers and mechanization became more sophisticated the work could become less stressful. Why didn’t it happen? Greed for profits…. leading to the 2008 financial crash in not-dissimilar circumstances to the crash of the 1930s. And then a skillfully-managed Establishment and Media campaign managed to deflect the blame for the consequent political decisions to impose AUSTERITY and blame OTHERS in order to help the financial institutions return to business as usual.Staring through the windows

I have some sympathy with the cries of Fake News these days, but I’m worried that the wrong news is being called fake news. In my opinion the last five years have seen a dreadful polarisation of stances in all the Media and our brains have not yet caught up with the bombardment of manipulation that comes our way in ever-increasingly sinister bits of brainwashing. The arguments on both sides of the EU referendum were not presented clearly or honestly and the claims of the “victors” (ie the Brexiters) are the ones that are now being strained. I blogged earlier that Time Will Tell but between that blog and now I am still waiting for the government to present certainty about what the post-Brexit world will be like. I hope clarity will start to emerge in the following weeks. What I am sure about is that much of what I think people thought they were voting for will not have changed. The rich will remain rich and will continue to get richer. The establishment will still protect itself and bolster itself. The only control that has been taken back will be the Haves controlling the Have-Nots. The disempowered and disenfranchised will still be staring through the windows of Thrushcross Grange wondering how it came to this.

|

| Fake News has been with us longer than The Donald.... |